Head in the Clouds, Alpha

I had a couple of people ask me about a recent post.

Their inquiry basically amounted to “Woah… are you ok?”

Truth be told, I was appreciating the picture on a “sometimes you can’t quite see where you’re going, but if you have the right tools, you’ll probably be OK”-level, not an apocalyptic “OMG We’re all going to die!”-level.

Plus, as I said, I really enjoy the composition.

Speaking of “IFR ahead,” as the blogosphere has become a permanent fixture of the InnerWebs, people have started diary-ing their various experiences while getting various airplane-related ratings.

I didn’t do any such thing for my private pilot’s license, probably because I had so many things going on in my life when I started, and I dragged it out for so long… but I thought I’d try and write a bit about my experience getting my IFR ticket…

(I’ll always make these as mostly-extended posts, since they’re not particularly Mozilla-specific.)

There’s a long standing debate about the length of time a pilot should wait between becoming VFR-licensed and starting work on an instrument rating. Some jump immediately into working onit, while others work on getting more flight time under their belt; some never become instrument rated.

I originally got into flying because I admired “The System” and its ability to move people, cargo, and planes safely around the country. You only use a very limited part of “The System” as a VFR-only pilot, and since I have something around 220 hours now, and I’ve been doing so many [night] cross countries lately that I already met the IFR rating’s cross-country pilot-in-command requirements before even starting training, I decided to jump into getting the rating only three months after I finished my PPL.

The first lesson involved a standard (and expected) review of the flight instruments that you stare at when you’re flying IFR; we focused on the pitot-static instruments (as opposed to the gyro instruments, which we looked at the next lesson).

At the end of the first lesson, we had a long, protracted discussion about what type of training I wanted to do, a discussion that you don’t really have as a PPL.

The first question was “steam gauges or glass”:

“But does it run Microsoft Flight Simulator?”

vs.

“Hello 1960s!”

I ended up picking steam gauges, because the skill you have to learn to use the gauges is the infamous “IFR Scan ™.” When you’re flying glass, you have to scan as well, but it’s a different scan, and in some ways, it’s arguably easier. Much like learning to navigate by NDB and VOR, and saving the GPS for later, I decided it would be easier to learn The Scan and transition to something more complicated (but, ironically, with easier instruments to scan) later. Also, the fact that our flight line only has one glass Cessna (but multiple Cessnas with steam gauges) on the flight line… “had nothing to do with it…”

The second question was “where do you want to get your charts?”

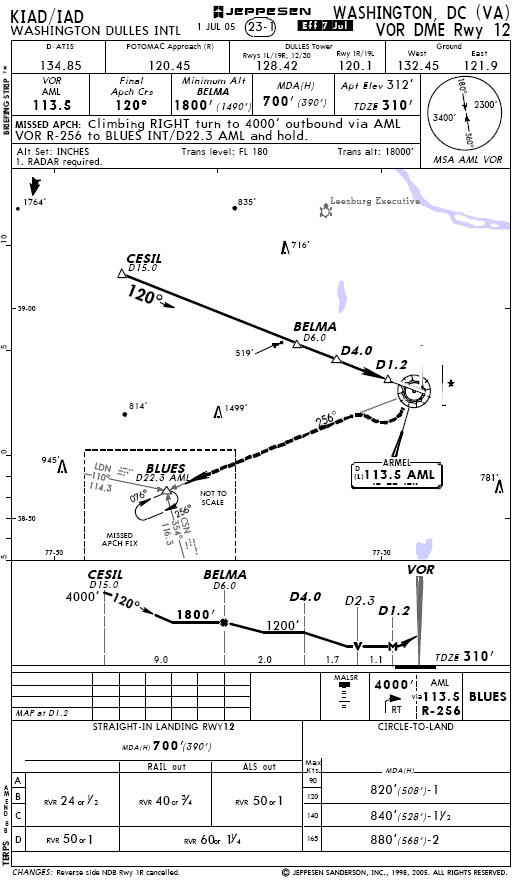

Jepp chart of the VOR/DME 12 Approach into Dulles |

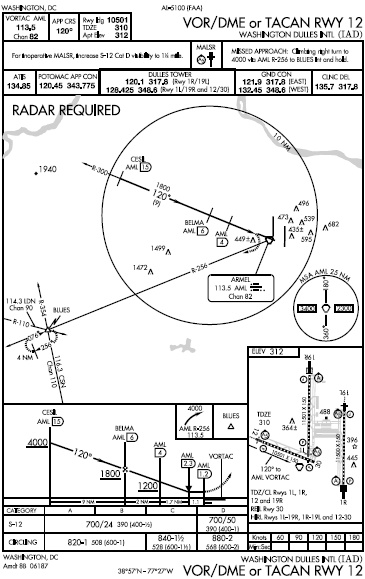

The FAA, obviously, publishes departure, en route, and approach charts (under the auspices of the fancily-named “National Aeronautical Charting Office.”) The other big vendor is Jeppesen.

Jepp charts are used by all the airlines, and they have some nice features, but they have a reputation of being more expensive. Interestingly enough, my instructor said that for a subscription to California-only, the Jepp charts and the NACO charts were about the same cost. He said he’s gone to Jepp charts for California, and NACO charts for the rest of the country.

In the end, they show you basically the same information, just presented slightly differently.

I punted on this decision, and decided to try to read both when I’m learning about charts, and decide when I’m forced to, based on which I find easier to utilize in the plane, on an approach.

NACO Chart of the same |

The differences between the charts are starting to be less relevant now, since the government is taking a hint from all those cognitive psychologists, and copying a lot of the niceties that made Jepp charts worth the added cost.

I finished my third IFR lesson tonight. It’s been the expected coverage of the gyro (and other instruments), plus some sim time performing exercises that teach precision aircraft control. These exercises turn out to be pretty boring, actually (things like flying in a racecar track-shape, using timed turns, vertical S-loops at constant airspeeds, etc.), but I shouldn’t really say that since I’m not very good at them.

The few things I have begun to internalize thus far:

- Your instruments are pretty much always trying to kill you… which is ironic, since IFR is all about “beliving in your instruments.”

- If you don’t stay IFR current, and then you find yourself flying home and stuck in an IFR situation and everything doesn’t go perfectly, your chances of dying—not just “oopsing” and having a bad day, of dying—go wayyyy up.

- Flying IFR is surprisingly tiring; part of the training is building up the stamina to focus on 6-8 instruments for hours at a time, but I’ve found that I become mentally exhausted after being in the sim for about an hour.

It’s kinda weird… I’m excited about the training, but every time I think about sitting in the sim, I sort of have this “Why am I doing this? I’d rather be at home, watching TV”-reaction. But then I still come back for another lesson.

At least for now.